Chairman of the Cricket Society of Scotland and of the Gala Water History and Heritage Association, local historian Fraser Simm, tells the story of flying machines and a link to a famous cricketer who came to the Borders 75 years ago.

THE cross currents of history often lap up on unusual shores.

The 100th anniversary of the first flight from Britain to Australia has links with the Borders and the south of Scotland.

At the end of the First World War in 1918 there was a surfeit of planes and pilots with time on their hands and this was followed by a flurry of long distance flights which echoed the days of the Portuguese sailors as they gradually made their way round Africa in the 15th century.

In July 1919 the milestone of the first crossing of the Atlantic Ocean by John Alcock and Arthur Brown was achieved. The success of this flight was the impetus for pioneer flights from London to Australia and Cape Town; and it is the former that is my subject.

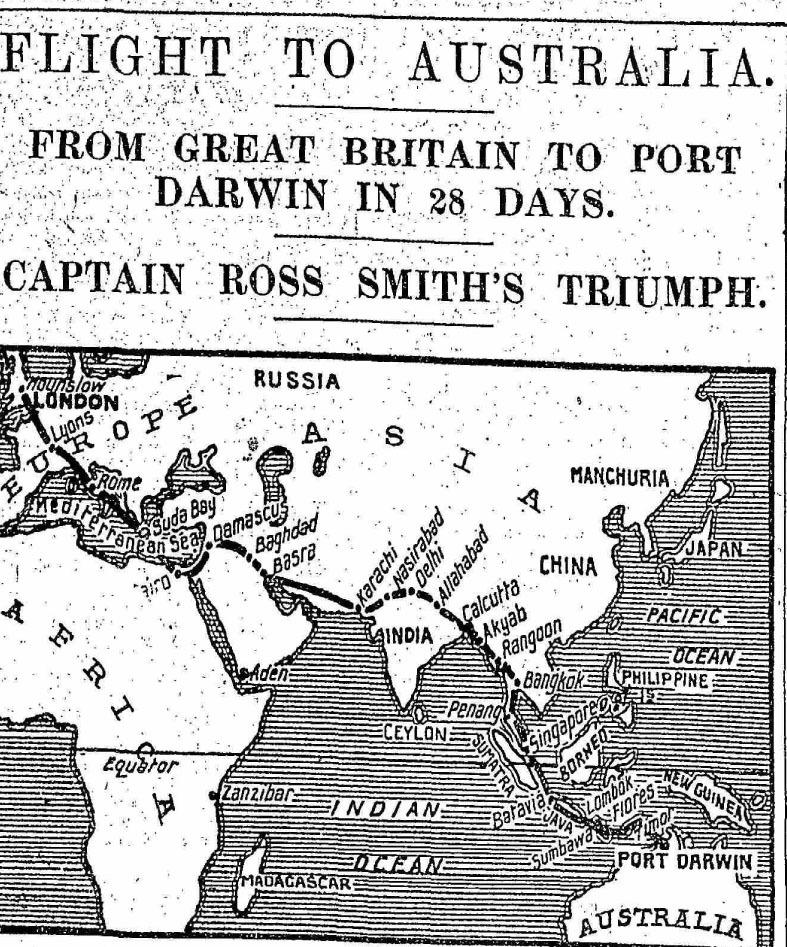

In May 1919 the Australian government offered a prize of £A10,000 for the first Australians in a British aircraft to fly from Great Britain to Australia. In November 1919 six entries started the race. Only two of these reached their final destination; the other four crashed in Surbiton, Corfu, Crete and Bali (the first two crashes resulted in crew fatalities).

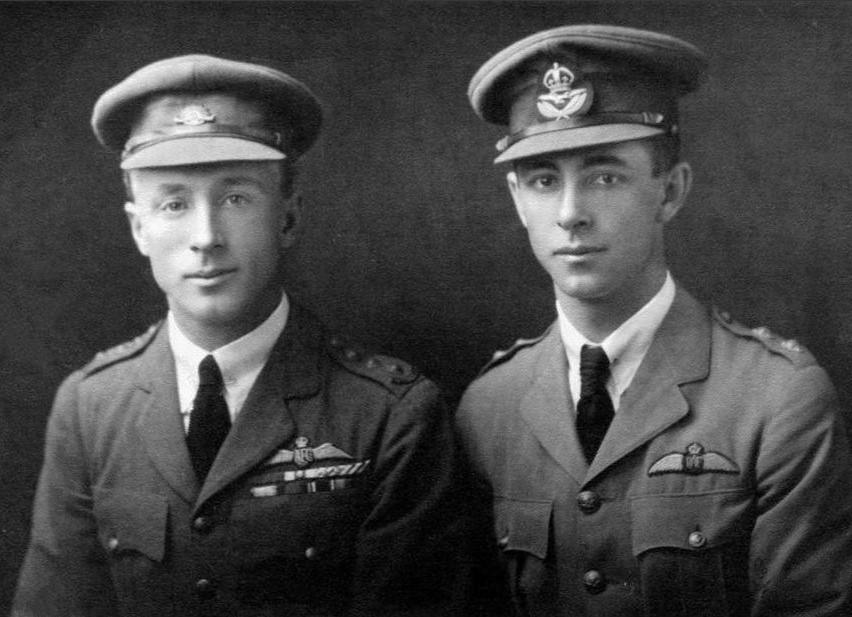

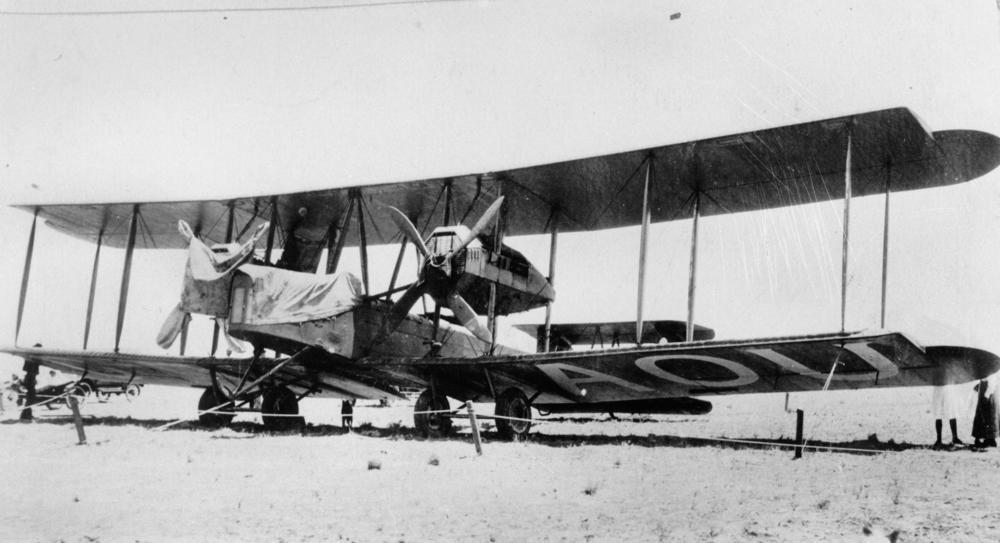

Of the two flights that succeeded, the clear winners were Ross and Keith Smith; they piloted a Vickers Vimy aeroplane and were joined by two mechanics, Wally Shiers and Jim Bennett. Their flight left Hounslow on November 12, 1919 and after 28 days and 11,123 miles they arrived at Darwin on December 10; stops included Lyon, Rome, Cairo, Damascus, Basra, Karachi, Delhi, Calcutta, Rangoon, Singora, Singapore, Batavia and Surabaya. This compares with just under four weeks that it took my grandparents to sail to Perth when they emigrated from Edinburgh to seek a new life in Australia in 1922 with help from the Assisted Passage Scheme.

Pilot Ross Smith had flown for T E Lawrence during the First World War and in 1918 he flew the first pioneering flight from Cairo to Calcutta which must have helped the record breaking journey the following year. The Smith brothers received knighthoods and the four members of the crew shared the prize of £A10,000. The runners up, who left London on January 8, 1920 took 206 days to reach Darwin, arriving in August 1920. These two flights compare with the recent “world’s longest flight” - 19 hour non-stop from New York to Sydney.

The two Smith brothers received a congratulatory telegram from the headmaster of small Scottish school,“Well done Ross and Keith; Warriston proud of you Mr F W Gardner headmaster”.

F Gardner was the headmaster of Warriston School in Moffat where the Smith brothers – and their sibling Colin – had spent the final two years of their education.

Ross and Keith Smith both had the middle name of their mother “Macpherson”; she was the daughter of an immigrant family from Scotland. Their father had been born in Moffat and emigrated to Western Australia, and in sending their three sons to Moffat to complete their education they were clearly strengthening their bonds with “the old country”.

The Smith brothers were therefore grounded in Scotland.

A well-known fact in the world of cricket is that the famous Australian all-rounder Keith Miller (born November 28, 1919) was named after the two Smith brothers; his parents named him Keith Ross Miller. It is not known whether Keith Miller realised that the Smith brothers had Scottish ancestry, but as he played wartime cricket matches in Scotland and visited again in 1948 it is nice to speculate. Miller’s wartime service as a mosquito pilot adds a certain symmetry to the achievements of his distinguished namesakes.

When he was in Scotland in 1945 playing for the RAAF, Miller lodged with the McVey family in Clovenfords and when he returned with “The Invincibles” in 1948 he planted a tree in Selkirk and called in on the family to renew his acquaintance.

In 2007 I paid a visit to Selkirk to see if I could see the tree planted by Miller but was told it had been destroyed in a storm - this story came full circle when I recently spoke to Hazel McLean who used to live in Clovenfords and had met Keith Miller in 1948 when he called on the McVeys.

She recalled being taken by her parents to their friends’ house nearby and the excitement in getting his autograph. On hearing this, I took a short journey to Clovenfords and was delighted to locate “the white house just before the bend” which is where the McVeys apparently resided.

Like many such encounters, only a smattering of memories remain but a little stardust goes a long, long way.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here